In June 1780, Molly Hogtrough’s kitchen on the edge of The Common probably consisted of an open fire and a large pot. Perhaps she even had a smaller saucepan and a skillet (if husband George hadn’t sold them to pay his gambling debts). And a kettle for her grandmother’s beloved tea would have been a blessing indeed.

While I was imagining how people lived back then, I wondered what Molly would have been able to cook for her family. I didn’t come up with much. Stew? A thick broth? Soup? Casserole? Yes, they are all variations of stews. Perhaps that’s where my love of one-pot cooking comes from.

Molly might have used turnips, carrots, peas, barley, or oats, and flavoured her stews with onions, and herbs collected from The Common – wild marjoram, thyme, mint, lemon balm, for example, but there are many more.

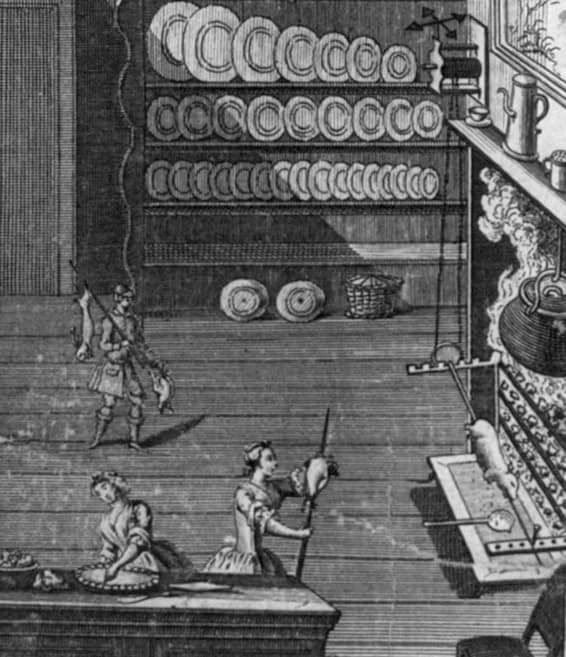

When they had a few coins spare, she would likely have added some scraps of meat. Basically, she could have boiled anything – meat, eggs, vegetables, or puddings, and made a sauce to go with her creations if she had been lucky enough to own that second pan. With a skillet her culinary world would really have opened up – frying tonight!

Her grandmother’s Elizabethan home most probably had no oven – they became popular in houses built a hundred years or so later, in the late 17th century. So, Molly could not make pies, cakes, or bread. Pancakes, or flatbreads, perhaps. She did not have a spit, either, but if George had been a shoemaker or a blacksmith and a little further up the social ladder, she may well have had one. And a range, too. Not the sprawling iron beast which the word conjures up today: doors to a small furnace and oven, and a hot plate on top. No, the 18th century range was what we would call a ‘grate’. Developed in the sixteenth century after coal became more popular as a fuel, it was basically a wrought-iron fire basket. It evolved into a large oblong basket on four legs and was fastened to the back of the chimney with tie bars. One could then roast large joints of meat via a spit which was attached to the front and sometimes turned mechanically by a clockwork spit jack.

But not for Molly these new-fangled contraptions. Granny’s house was too old, much more basic, and they were just too poor.

I recently bought a booklet published in 1985 by English Heritage entitled ‘Food and Cooking in 18th Century Britain, History and Recipes’ by Jennifer Stead. It is an interesting read for someone with their head stuck in 1780. Ms. Stead packs a lot of information into fifty pages. She tells us about various cooking methods for the different classes of society, the utensils and other equipment they had available, and how food was stored and prepared. I now know how to serve a hare! I’m sure I’ll never need that little nugget of information, but it was interesting, nonetheless.

The second half of the book includes the recipes.

Now I can really get inside Molly’s head and find out what her fingers were itching to cook, if she could get them to stop reaching for that flask of gin on the mantelpiece for a moment.

The first recipe is plain pudding, boiled or baked. I’m going to tackle it – the boiled version anyway, since Molly had no oven.

It seems so simple. The ingredients are already in my store cupboard: plain flour, salt, eggs, milk or single cream. The one thing I don’t have is a pudding cloth, but I’m sure my local supermarket will have one for a pretty penny.

This recipe calls for it to be served at once with meat (not for me, thanks) or as a dessert (yes, please) with hot wine sauce.

My mouth is watering as I type. I think.